← Back to blogs

Whitechapel and the Project

Katelyn Leece - October 23, 2017

No matter how many years went by since Jack the Ripper disappeared without a trace, there seemed to be a constant and widespread belief that “[he] did not bind himself to any locality in continuing his ‘work.’”1 When it looked like the murders of two women in Essex during the spring of 1893 would go unsolved, the press began perpetuating paranoid perceptions out of fear that the Ripper’s brutality had reared its ugly head and struck again.

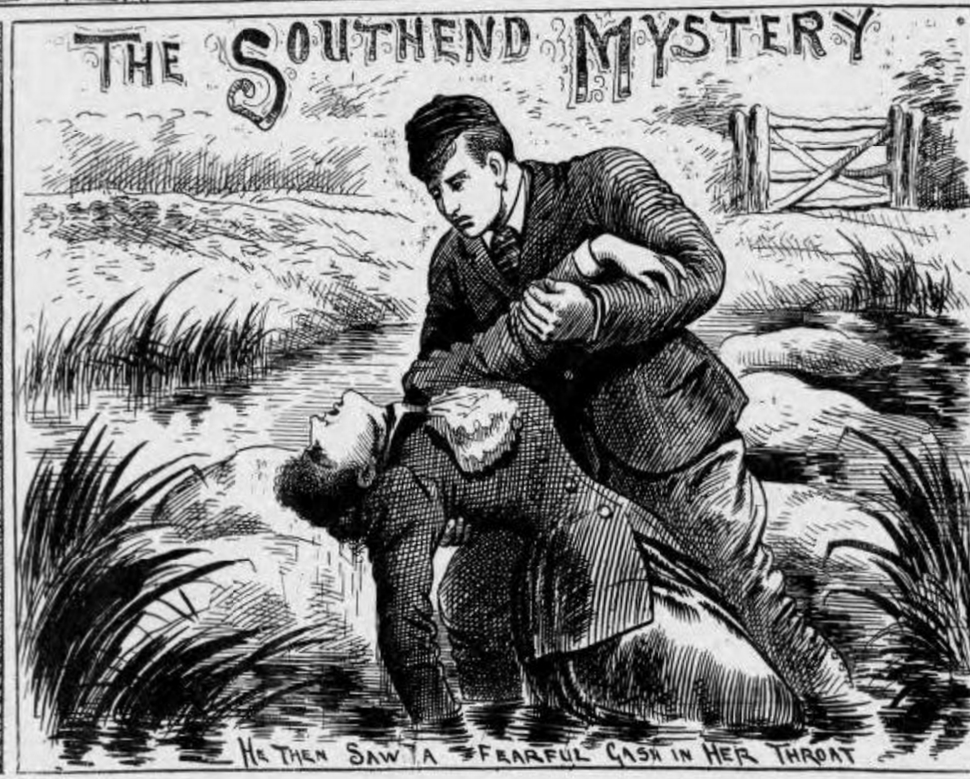

On May 20th, Alfred Hazell was walking along the path near the parish church of Rochford and came across Mrs. Emma Hunt lying in the mud at the edge of the brook. Still alive and breathing, the 40-year-old widow had “a fearful gash in her throat” and belongings strewn about her, but she had already drawn her last breath by the time the young man returned with help.2

With no other viable suspects, the local community was quick to assume Hazell himself was the murderer and officials committed him for trial. However, he was eventually released due to insufficient evidence without anyone to take his place – the mysterious murder was left unsolved.3

“The Southend Mystery,” Illustrated Police News (3 June 1893) p. 1

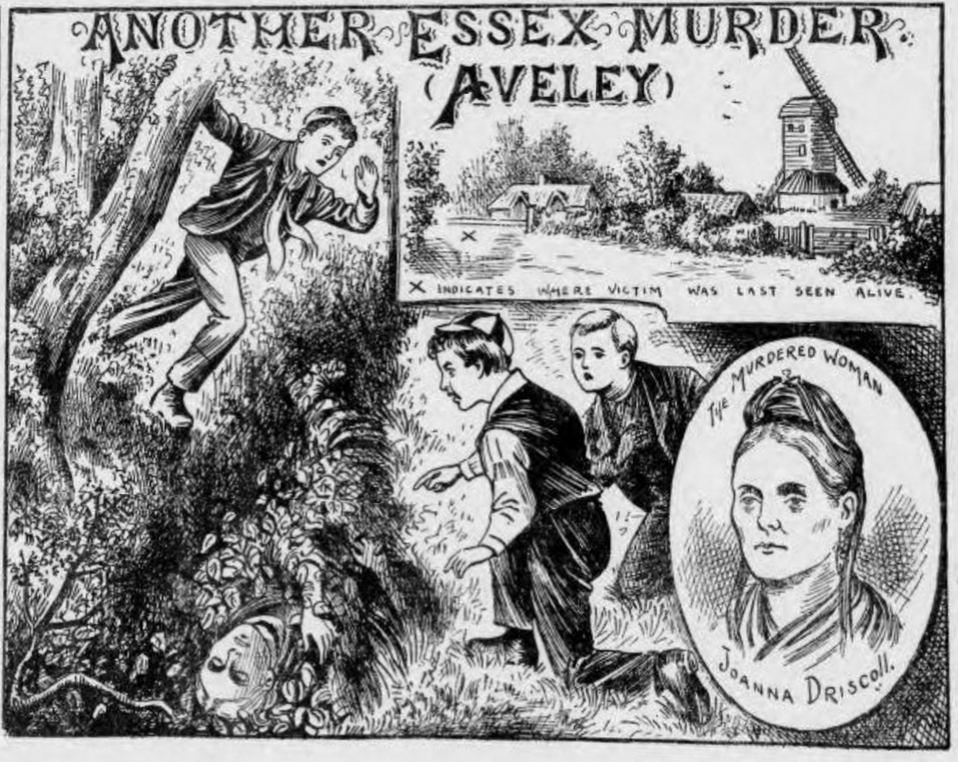

It was not long after that on June 1st when three young boys stumbled upon the dead body of a woman with a mangled face and a slit throat in a ditch on the side of the road into Grays. Just like Emma Hunt, Joanna Driscoll was a middle-aged widow of reputable standing and had visited Essex with her daughter to go pea picking.

Witnesses say they saw her alone at night with a man in dark army clothing, but, despite making three arrests in the weeks following her murder, the police never found her killer.4

“Another Essex Murder,” Illustrated Police News (10 June 1893) p. 1

Was Jack Back?

The public became unsettled after months went by without any answers to the respective mysteries at Rochford and Grays. One writer for The Daily Chronicle asked a question in August of that year which spread mass panic among the press of the United Kingdom: “Is ‘Jack the Ripper’ About Again?”5

The Essex murders “for which there [seemed] no likelihood that anybody will be brought to justice”6 were similar enough to the infamous Whitechapel murders that, for a time, made them obsessed with uncovering the answer. Underscoring that it was in the realm of possibility, the recurring article compares the silent five-minute murder of Mrs. Hunt and the ease of escape by Mrs. Driscoll’s killer to the Ripper’s impossible speed and silence in his Mitre Square murder five years prior. Contradictory evidence, such as the victims’ social status and lack of extreme mutilation, was conveniently set aside to solidify their claims.7

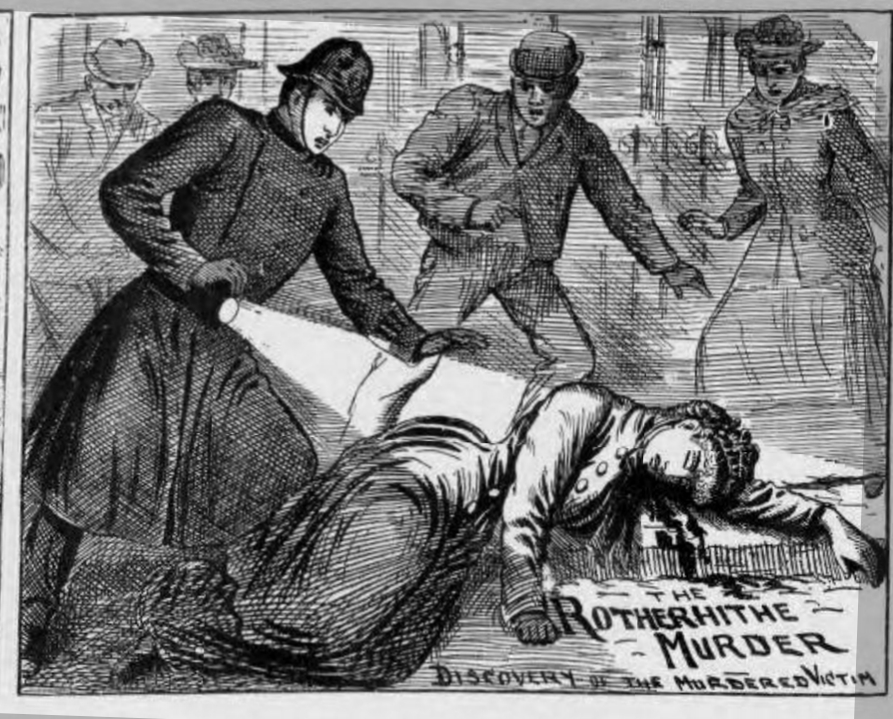

In fact, the events surrounding the murder of Jenny Hinks a couple of months later in Rotherhithe make it seem as though this scapegoat was avoided entirely if they apprehended the one who was responsible. The state of her body resembled the “fiendish crimes that have made Whitechapel a byeword,”8 but the culprit was soon found and convicted. The Italian sailor couldn’t have possibly committed the Essex murders, let alone be Jack the Ripper himself9 – all comparisons between this case and the infamous murderer ceased and desisted.

“The Rotherhithe Murder,” Illustrated Police News (8 July 1893), p. 1.

A Never-Ending Story

Unlike the mysteries of fictional monsters that terrified readers from a safe distance as inked words on a page, Victorians never could have escaped the threat of Jack the Ripper by simply closing the hard covers of a heavy leather-bound book. Instead, the mangled bodies of women in the streets across the country and the evasive murderers who killed them served as reminders that this monster was, in fact, very real.

- 1 “‘Jack the Ripper’ and the Rochford Murder,” Dundee Evening Telegraph (12 August 1893) p. 2; also found in Sheffield Evening Telegraph (11 August 1893), Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough (14 August 1893), Shields Daily Gazette (14 August 1893).

- 2 “The Rochford Murder,” East Anglian Daily Times (27 May 1893) p. 5; “Mysterious Murder of a Widow,” Reynolds’s Newspaper (28 May 1893) p. 4.

- 3 “The Rochford Murder,” Globe (25 July 1893) p. 7; “Bill Thrown Out,” Essex Herald (25 July 1893) p. 5.

- 4 “Another Essex Mystery,” Globe (3 June 1893) p. 2.

- 5 “Is Jack the Ripper About Again?” Aberdeen Evening Express (12 August 1893) p. 2; also found in the Glasgow Evening Post (11 August 1893), Aberdeen Press and Journal (14 August 1893), and under “A Jack the Ripper Scare” in Newry Reporter (15 August 1893).

- 6 “Jack the Ripper and Recent Murders,” Gloucestershire Echo (12 August 1893) p. 4.

- 7 “Is Jack the Ripper About Again?” Sheffield Evening Telegraph (11 August 1893) p. 3; also found with a few extra details under the same title in Shields Daily Gazette (14 August 1893), Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough (14 August 1893), and under “‘Jack the Ripper’ and the Rochford Murder” in Dundee Evening Telegraph (12 August 1893).

- 8 “The Rotherhithe Murder,” Illustrated Police News (8 July 1893) p. 2.

- 9 “The Rotherhithe Murder,” South London Press (12 August 1893) p. 5.