The Press

Victorian newspapers

The late Victorian newspaper is an unparalleled resource to understand public discussion and debate on a wide variety of topics. Newspapers were within reach of most Britons, and were readily available across the nation. The Forster Act of 1870 mandated ele mentary education to all children, thus by 1885 the literacy rates were high. Literacy rates are hard to pin down, but there is a very clear and striking increase over the second half of the nineteenth century. Men’s literacy rates increased almost thirty percent and women’s increased over forty percent between 1851 and 1900 according to census data.1 Technological advances and the repeal of the stamp duty helped aid in the creation of new papers and their mass distribution.2 By 1885 there were six morning papers and five evening papers in London alone. A London journalist could turn to two dozen daily papers to sell his stories.3

mentary education to all children, thus by 1885 the literacy rates were high. Literacy rates are hard to pin down, but there is a very clear and striking increase over the second half of the nineteenth century. Men’s literacy rates increased almost thirty percent and women’s increased over forty percent between 1851 and 1900 according to census data.1 Technological advances and the repeal of the stamp duty helped aid in the creation of new papers and their mass distribution.2 By 1885 there were six morning papers and five evening papers in London alone. A London journalist could turn to two dozen daily papers to sell his stories.3

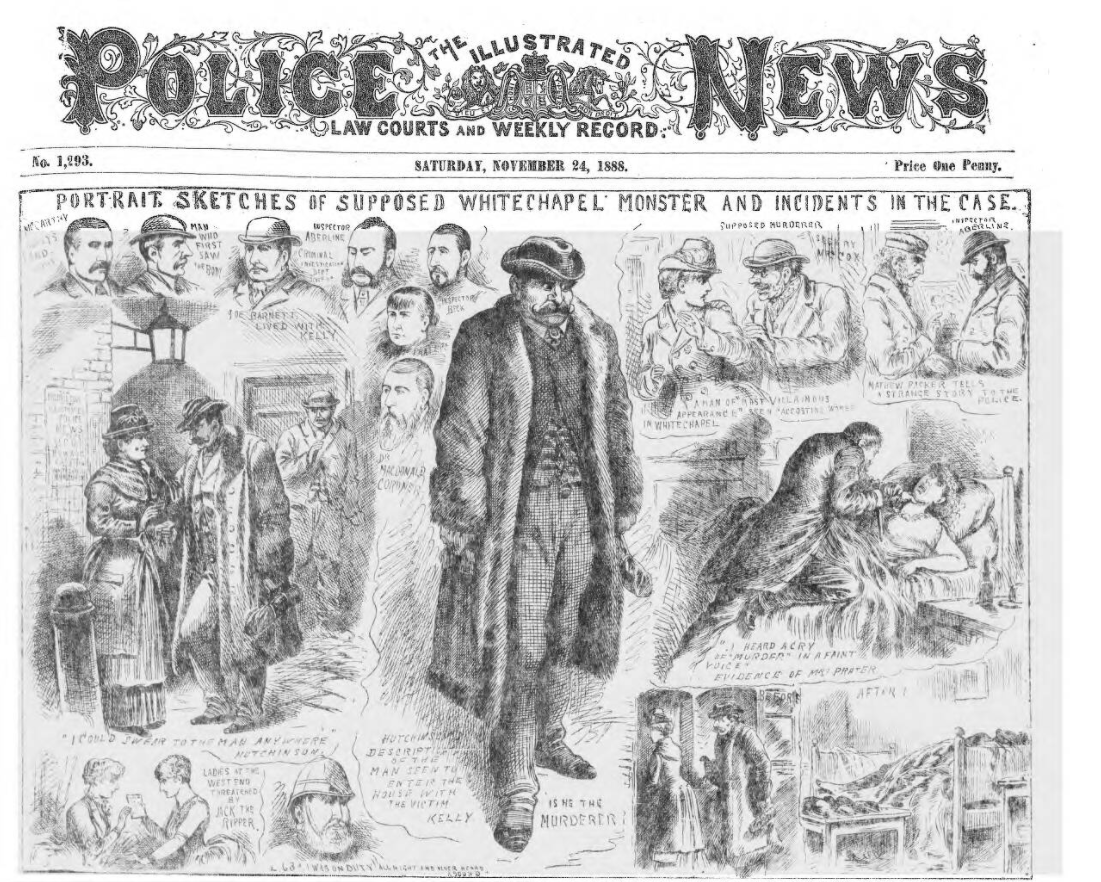

An increasingly competitive newspaper marketplace led to an aggressive news cycle with editors clamouring for ever more dramatic stories. There was a newspaper for every price point, political inclination, and attention span. Stories of violence and murder sold particularly well, and thus it should be no surprise that the spectacularly violent Whitechapel murders garnered much press attention.4 However, these were not the only Whitechapel stories that hit the papers. Murders made headlines; but mundane stories of Whitechapel also populated the pages of the daily and weekly papers before and after these murders

Writing in 1887, poet and critic Matthew Arnold, was both cheered by the expansion of the press, and wary of some of its newest incarnations.

[Journalism] has much to recommend it; it is full of ability, novelty, variety, sensation, sympathy, generous instincts; its one great fault is that it is feather-brained. It throws out assertions at a venture because it wishes them true; does not correct either them or itself; if they are false; and to get at the state of things as they truly are seems to feel no concern whatever. 5

While traditional journalism was a force for good in the world, he worried about new styles and approaches that fell under the category of “New” or “Sensation” Journalism.

Sensation journalism

The focus of Arnold’s ire were journalists like W.T. Stead who not only defended, but embraced the idea of a very different approach to print media.

Everything that is of human interest is of interest to the Press. A newspaper, to put it brutally, must have good copy, and good copy is oftener found among the outcast and the disinherited of the earth than among the fat and well-fed citizens. Hence selfishness makes the editor more concerned about the vagabond, the landless man, and the deserted child, than the member. He has his Achilles' heel in the advertisements, and he must not carry his allegiance to outcast humanity too far. …

It is the fashion, among those who decry the power of the more advanced journalism of the day, to sneer at each fresh development of its power as mere sensationalism. This convenient phrase covers a wonderful lack of thinking. For, after all, is it not a simple fact that it is solely by sensations experienced by the optic nerve that we see, and that without a continual stream of ever-renewed sensations we should neither hear, nor see, nor feel, nor think. Our lives, our thought, our existence, are built up by a never-ending series of sensations, and when people object to sensations they object to the very material of life.6

Sensation journalism was a phenomenon in 1885, the same year of W.T. Stead’s infamous “Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon” four-part exposé of child sex trafficking. Given some of the critiques levied against New Journalism, it would be easy to assume that before the 1880s, the media did not report on violence and depravity. However, the broadsides and chapbooks of fifty years earlier were as full of suicides, murders, maiming and gore as anything that followed. The late eighteenth century Newgate Calendar, with its stories of crime, trials and executions, was unparalleled in terms of its popularity and endurance.7

New Journalism believed that the press should not only report, but actively be the social conscious of the nation. With a newly literate and larger electorate, the press could help shape the voice and opinions of these new voters and readers. They believed the press could be a pulpit for public opinion to help shape government, and make it more responsive to the people’s will.8 Rather than attempting to be dispassionate, New Journalism was personal, and appealed to readers on their own terms. It engaged its readers in new ways as it “evoked comment, invited speculation and engendered passions.”9

Sensation journalism wasn’t only about reporting crime and murder, it was also about highlighting human interest stories, and emphasizing the nuanced and complicated contexts of news events. The biases of such reports are evident, and are incredibly useful in trying to unpack the moral value ascribed to people, behaviours, and even neighborhoods.10 And while moralists decried the journalism of the 1880s and 1890s as lurid and callous, it was extraordinarily popular. And often those who claimed to be the most offended one moment were the first to follow a story of horror and gore the next.

What’s Missing

The newspapers that form the basis of this mapping project are varied and representative of a number of communities; however, the list is not exhaustive. The British Newspaper Archive is extensive, but is still missing a number of important papers. The most pressing omissions for the purposes of this project are Jewish newspapers including the Yiddish language Der Arbeter Fraynd and the English Jewish Chronicle. Tit-Bits was successful and cheap, and in many ways the precursor to a more popular style of journalism.11 It and other weekly newspapers and more specialist periodicals are not part of the BNA collection, even though they may have been important cultural influencers.

Some of these oversights can be corrected in other areas of the project; Tit-Bits, for example, was read for some images and longer pieces about Whitechapel and the East End. However, if papers are not digitized, they cannot be scanned and integrated into the project in the same way. The ability of Optical Character Recognition to almost instantly scan thousands of pages of information would take a prohibitive amount of time for the average reader. Here the human eye is at an extreme disadvantage. Some of these periodicals and newspapers may eventually be integrated into searchable databases, but as of 2018 this project has its limits of data.

- 1 Men’s literacy rate was 97.2 percent and women’s was 96.8 percent by 1900. Richard D. Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900, 2nd edn (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2nd ed. 1998).

- 2 Judith Rowbotham, Kim Stevenson, and Samantha Pegg, Crime News in Modern Britain: Press Reporting and Responsibility, 1820–2010 (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 39.

- 3 John Stokes, In the Nineties (University of Chicago Press, 1989), 17.

- 4 Kevin Williams, Get Me a Murder a Day! A History of Mass Communications in Britain (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 1997).

- 5 Matthew Arnold, “Up to Easter,” Nineteenth Century, May 1887, 638-639.

- 6 W.T. Stead, “Government by Journalism,” The Contemporary Review 49 (1886), 653-674.

- 7 L. Perry Curtis, Jack the Ripper and the London Press, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 68.

- 8 J. O. Baylen, “The ‘New Journalism’ in Late Victorian Britain,” The Australian Journal of Politics and History 18 (1972), 369.

- 9 Stephen Koss, Rise and Fall of the Political Press v. 1 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1981), 343.

- 10 Stokes, In the Nineties, 19.

- 11 Bridget Griffen-Foley, “From Tit Bits to Big Brother: A Century of Audience Participation in the Media,” Media Culture and Society 26, no. 4 (2004): 533-548.